Evil and Theism

Proofs of Non-existence • There are two ways to prove non-existence: Logical Nothing is X because X is impossible; its concept involves a contradiction. Evidential It is likely that nothing is X because we don’t see evidence Y and we would expect to see Y if X existed. • Logical non-existence arguments try to show that things like square-circles or the Barber of Saxony cannot exist for purely conceptual reasons. • Evidential arguments try to show non-existence based on an absence of evidence; when we see flags and leaves not moving, we infer an absence of wind. • Evidential arguments are only good to the extent that we would expect to see the evidence; not seeing germs does not give you good evidence against the existence of germs. • Arguments from evil against the existence of God have taken both logical and evidential forms.

The Initial Probability • We have discussed earlier in the class how evidence needs to update based on prior probabilities. • In the absence of evidence one way or another, one might think that one should just stick with an initial probability judgment. • This raises the question, what initial probability should one assign to the claim that God exists?

The Initial Probability • One suggestion is that we should always start 50/50, not assuming truth or falsity. • This is famously countered by the example of Russell’s teapot: Many orthodox people speak as though it were the business of sceptics to disprove received dogmas rather than of dogmatists to prove them. This is, of course, a mistake. If I were to suggest that between the Earth and Mars there is a china teapot revolving about the sun in an elliptical orbit, nobody would be able to disprove my assertion provided I were careful to add that the teapot is too small to be revealed even by our most powerful telescopes. But if I were to go on to say that, since my assertion cannot be disproved, it is intolerable presumption on the part of human reason to doubt it, I should rightly be thought to be talking nonsense. –Bertrand Russell • In many cases, such as the teapot, or fairies, or leprachauns, we want to assign a much lower probability than 50% (though probably not 0).

The Initial Probability • One suggestion is that we should always start 50/50, not assuming truth or falsity. • A second suggestion would be to assume the non-existence of things and require evidence to move you towards believing in existence. • However, this also seems false. • Consider a glass of milk which has sat on the counter for two days at room temperature. What probability should you assign to there being harmful bacteria in the milk? • If you follow the principle of always assuming non-existence until you have evidence to the contrary, then you should assume there is no harmful bacteria (and hence you should be willing to drink the milk), but clearly this is crazy.

The Initial Probability • How do we reconcile intuitions about the teapot and the bacteria? • One suggestion is that it is explained by our beliefs regarding how certain things came to be. • A teapot is an artifact − something made by people • If a teapot is orbiting the Sun, then it must have somehow gotten launched there by someone, and we are able to assign incredibly low probabilities to the various scenarios in which we can imagine that happening. • Similarly, we can assign low probabilities to leprechauns because we assign low probabilities to the scenarios in which evolution brings about a creature with the abilities of a leprechaun.

The Initial Probability • How do we reconcile intuitions about the teapot and the bacteria? • One suggestion is that it is explained by our beliefs regarding how certain things came to be. • On the other hand, we think it quite easy for bacteria to come to be in warm milk, so we assign that a relatively high probability. • Such an account says that we should assign higher initial probability to a sasquatch or the Loch Ness monster than to leprechauns, since the scenarios that bring them about are more likely than the scenarios which bring about Leprechauns.

The Initial Probability • What should we then assign as the initial probability of the God hypothesis? • If God is taken to be the creator of the whole universe, then we struggle to apply our “origin” criterion to God. • Also, many think that if God exists, God’s existence is necessary, and we can really only assign initial probabilities to contingent things.

God • People have tried to disprove God in both the Evidential way and the Logical way • For the sake of having an agreed upon target, philosophers generally agree that there is a God if and only if there is a being that is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent. • While it is not always clear exactly how much these properties line up with various religious traditions, it seems that most classic monotheisms would say that God is unbounded with respect to good things, and that power, knowledge, and moral goodness are all good things − hence the definition. • There have been attempts to show that each of the omni-properties is impossible. • If one shows that it is conceptually impossible for there to be an omnipotent, omniscient, omnibenevolent, then one has given a logical argument for the non-existence of God.

The Paradox of Omnipotence (1) If God is omnipotent, then there is nothing he cannot do. (2) Either God can or cannot create a rock so big he cannot lift it. (3) If God can create a rock so big he cannot lift it, then there is something he cannot do. (4) If God cannot create a rock so big he cannot lift it, then there is something he cannot do. (5) Therefore, there is something God cannot do (2, 3, 4) (6) Therefore, God is not omnipotent (1, 5)

Omnipotence The biggest question about the argument is, how should we understand omnipotence? Consider these potential definitions 1. X is omnipotent iff every sentence is such that X could make it true. 2. X is omnipotent iff every meaningful sentence is such that X could make it true. 3. X is omnipotent iff X can any action that is broadly logically possible. 4. X is omnipotent iff X can do anything suitable to a perfect being (so X cannot sin, tempt, etc.) Responses 2 and 3 try to say that an omnipotent being can do everything , but that there is a sense in which ‘making a rock so big God cannot move it’ doesn’t count as a thing.

The Liar Paradox • Some people have attempted to use the liar paradox to solve the omnipotence paradox • The Liar Paradox: “this sentence is false.” • Clearly we cannot say that the sentence is true, but if it is false, then it is true, so we cannot say it is false. • One response is to say that it is meaningless. It is just as meaningless as “ ’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe.” • It seems weird that individual meaningful words could combine to be meaningless, but perhaps this is the case. • If one takes this route, then it is plausible that “rock so big God cannot move it” is meaningless.

The Paradox of Omnipotence (1) If God is omnipotent, then there is nothing he cannot do. ? (2) Either God can or cannot create a rock so big he cannot lift it. (3) If God can create a rock so big he cannot lift it, then there is something he cannot do. (4) If God cannot create a rock so big he cannot lift it, then there is something he cannot do. ? (5) Therefore, there is something God cannot do (2, 3, 4) (6) Therefore, God is not omnipotent (1, 5)

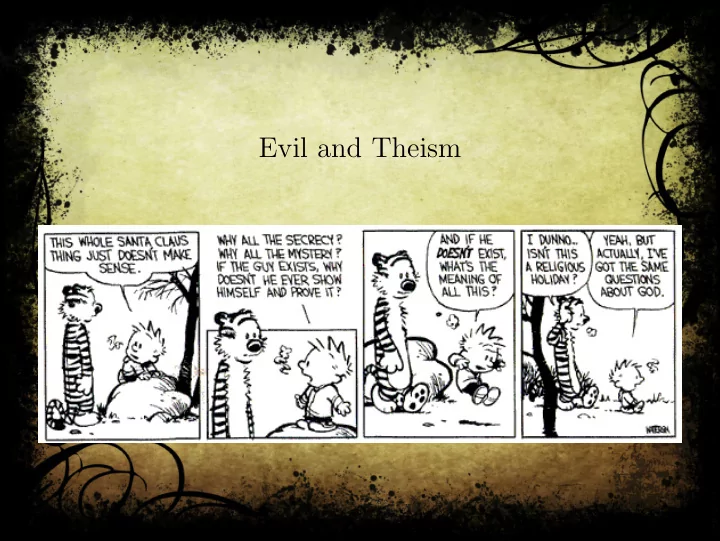

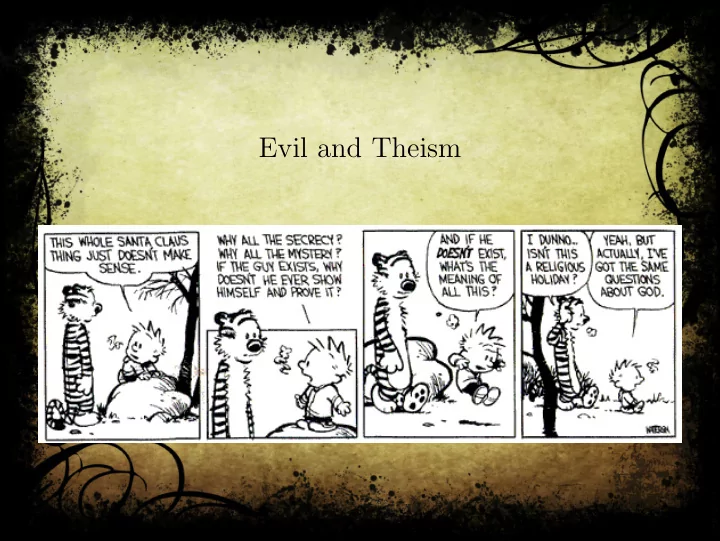

• There are seemingly unlimited ways to argue from the existence of evil to the non-existence of God. • Some forms of the argument are Logical problems which say that, even if the concept of God is not contradictory, the concept of a God that allows evil is contradictory. • Others merely argue that if there were a God, we would expect to see a world much different than our own, so we have strong evidence of the non-existence of God. • We will look at a version of each

The Logical Problem of Evil (1) If God exists, then God is all good, all powerful, and all knowing and allows there to be evil in the world. (2) If God is all good, then he would want to eliminate evil. (3) If God is all powerful, then he can eliminate evil. (4) If God is all knowing, then he is aware of any evil that exists. (5) Evil exists. (C) Therefore, God does not exist. Is this valid?

The Logical Problem of Evil (1) If God exists, then God is all good, all powerful, and all knowing and allows evil. (2) If God is all good, then he would want to eliminate evil. (3) If God is all powerful, then he can eliminate evil. (4) If God is all knowing, then he is aware of any evil that exists. (5) If there is a being that knows about all evil, wants to eliminate evil, and is able to eliminate all evil, then that being would not allow there to be any evil in the world. (6) Evil exists. (C) Therefore, God does not exist. Should we think that premise 5 is true?

Recommend

More recommend