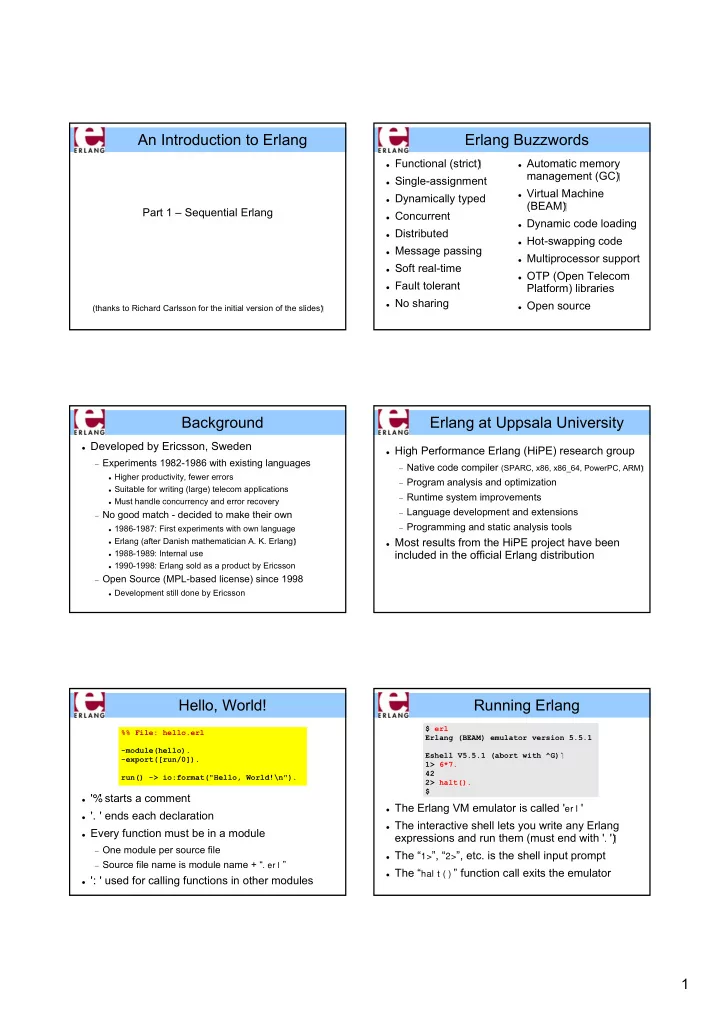

An Introduction to Erlang Erlang Buzzwords � Functional (strict) � Automatic memory management (GC) � Single-assignment � Virtual Machine � Dynamically typed (BEAM) Part 1 – Sequential Erlang � Concurrent � Dynamic code loading � Distributed � Hot-swapping code � Message passing � Multiprocessor support � Soft real-time � OTP (Open Telecom � Fault tolerant Platform) libraries � No sharing � Open source (thanks to Richard Carlsson for the initial version of the slides) Background Erlang at Uppsala University � Developed by Ericsson, Sweden � High Performance Erlang (HiPE) research group − Experiments 1982-1986 with existing languages − Native code compiler (SPARC, x86, x86_64, PowerPC, ARM) � Higher productivity, fewer errors − Program analysis and optimization � Suitable for writing (large) telecom applications − Runtime system improvements � Must handle concurrency and error recovery − Language development and extensions − No good match - decided to make their own − Programming and static analysis tools � 1986-1987: First experiments with own language � Erlang (after Danish mathematician A. K. Erlang) � Most results from the HiPE project have been � 1988-1989: Internal use included in the official Erlang distribution � 1990-1998: Erlang sold as a product by Ericsson − Open Source (MPL-based license) since 1998 � Development still done by Ericsson Hello, World! Running Erlang $ erl %% File: hello.erl Erlang (BEAM) emulator version 5.5.1 -module(hello). Eshell V5.5.1 (abort with ^G) -export([run/0]). 1> 6*7. 42 run() -> io:format("Hello, World!\n"). 2> halt(). $ � ' % ' starts a comment � The Erlang VM emulator is called ' er l ' � ' . ' ends each declaration � The interactive shell lets you write any Erlang � Every function must be in a module expressions and run them (must end with ' . ') − One module per source file � The “ 1> ”, “ 2> ”, etc. is the shell input prompt − Source file name is module name + “ . er l ” � The “ hal t ( ) ” function call exits the emulator � ' : ' used for calling functions in other modules 1

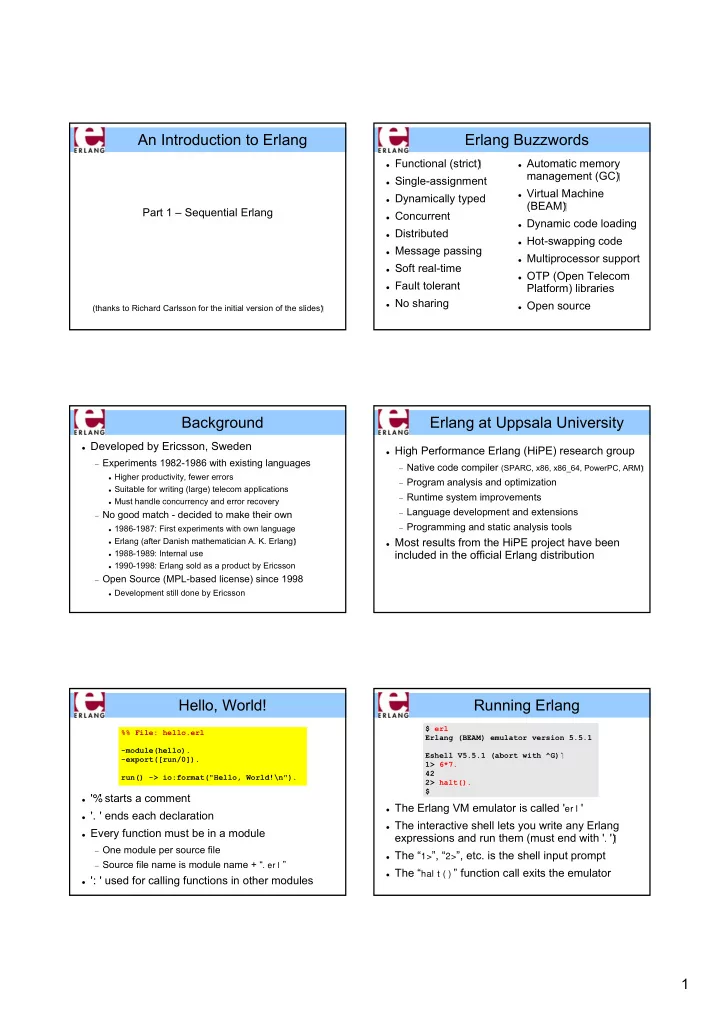

Compiling a module Running a program $ erl Eshell V5.5.1 (abort with ^G) Erlang (BEAM) emulator version 5.5.1 1> c(hello). {ok,hello} Eshell V5.5.1 (abort with ^G) 2> hello:run(). 1> c(hello). Hello, World! {ok,hello} ok 2> 3> � The “ c(Module) ” built-in shell function compiles a � Compile all your modules module and loads it into the system � Call the exported function that you want to run, − If you change something and do “ c(Module) ” again, using “ module:function(...). ” the new version of the module will replace the old � The final value is always printed in the shell � There is also a standalone compiler called “ erlc ” − “ ok ” is the return value from io:format(...) − Running “ erlc hello.erl ” creates “ hello.beam ” − Can be used in a normal Makefile A recursive function Tail recursion with accumulator -module(factorial). -module(factorial). -export([fac/1]). -export([fac/1]). fac(N) when N > 0 -> fac(N) -> fac(N, 1). N * fac(N-1); fac(0) -> fac(N, Product) when N > 0 -> 1. fac(N-1, Product*N); fac(0, Product) -> � Variables start with upper-case characters! Product. � ' ; ' separates function clauses � The arity is part of the function name: fac/1 ≠ fac/2 � Variables are local to the function clause � Non-exported functions are local to the module � Pattern matching and guards to select clauses � Function definitions cannot be nested (as in C) � Run-time error if no clause matches (e.g., N < 0) � Last call optimization: the stack does not grow if the result is the value of another function call � Run-time error if N is not an integer Recursion over lists List recursion with accumulator -module(list). -module(list). -export([reverse/1]). -export([last/1]). reverse(List) -> reverse(List, []). last([Element]) -> Element; last([_|Rest]) -> last(Rest). reverse([Head|Tail], Acc) -> � Pattern matching selects components of the data reverse(Tail, [Head|Acc]); reverse([], Acc) -> � “_” is a “don't care”-pattern (not a variable) Acc. � “ [ Head| Tai l ] ” is the syntax for a single list cell � The same syntax is used to construct lists � “ [ ] ” is the empty list (often called “nil”) � Strings are simply lists of character codes � “ [ X, Y, Z] ” is a list with exactly three elements − "Hello" = [$H, $e, $l, $l, $o] = [72,101,...] � “ [ X, Y, Z| Tai l ] ” has three or more elements − "" = [] 2

Numbers Atoms 12345 true % boolean -9876 false % boolean 16#ffff ok % used as “void” value 2#010101 hello_world $A doNotUseCamelCaseInAtoms 0.0 'This is also an atom' 3.1415926 'foo@bar.baz' 6.023e+23 � Must start with lower-case character or be quoted � Arbitrary-size integers (but usually just one word) � Single-quotes are used to create arbitrary atoms � # -notation for base-N integers � Similar to hashed strings � $ -notation for character codes ( ISO-8859-1 ) − Use only one word of data (just like a small integer) � Normal floating-point numbers (standard syntax) − Constant-time equality test (e.g., in pattern matching) − cannot start with just a ' . ', as in e.g. C − At run-time: atom_to_list(Atom) , list_to_atom(List) Tuples Other data types � Functions � No separate booleans {} {42} − atoms true / false − Anonymous and other {1,2,3,4} {movie, "Yojimbo", 1961, "Kurosawa"} � Bit streams � Erlang values in {foo, {bar, X}, general are often {baz, Y}, − Sequences of bits [1,2,3,4,5]} called “terms” − <<0,1,2,...,255>> � Tuples are the main data constructor in Erlang � All terms are ordered � Process identifiers � A tuple whose 1 st element is an atom is called a and can be compared − Usually called 'Pids' tagged tuple - this is used like constructors in ML with <, >, ==, =:=, etc. � References − Just a convention – but almost all code uses this − Unique “cookies” � The elements of a tuple can be any values − R = make_ref() � At run-time: tuple_to_list(Tup) , list_to_tuple(List) Type tests and conversions Built-in functions (BIFs) � Note that is_list only � Implemented in C is_integer(X) length(List) is_float(X) tuple_size(Tuple) looks at the first cell of � All the type tests and is_number(X) element(N, Tuple) the list, not the rest is_atom(X) setelement(N, Tuple, Val) conversions are BIFs is_tuple(X) � A list cell whose tail is is_pid(X) abs(N) � Most BIFs (not all) are not another list cell or is_reference(X) round(N) in the module “ erlang ” is_function(X) trunc(N) an empty list is called is_list(X) % [] or [_|_] � Many common BIFs an “improper list”. throw(Term) are auto-imported atom_to_list(A) halt() − Avoid creating them! list_to_tuple(L) (recognized without binary_to_list(B) time() � Some conversion writing “ erlang: ... ”) date() functions are just for term_to_binary(X) now() � Operators (+,-,*,/,...) binary_to_term(B) debugging: avoid! self() are also really BIFs spawn(Function) − pid_to_list(Pid) exit(Term) 3

Recommend

More recommend